(Originally published in the San Antonio Express-News as a Father’s Day Tribute

and then, later, in Grief Digest magazine)

Note: My father was still alive when the article was published in the San Antonio Express News. He was so proud to be honored. The essay appeared on the front page of art

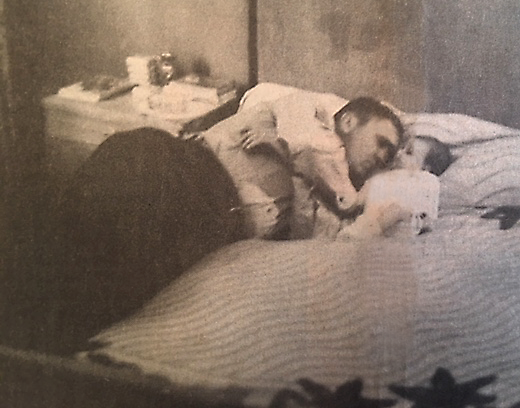

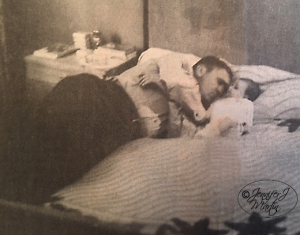

As I look at the old black and white photograph of him and me, I see an image of a handsome young man, age thirty-five, and his infant daughter. We lie side by side on a soft, chenille bedspread. He is asleep, turned on his left side facing me. His arms are folded across his chest, slightly creasing the front of his starched, khaki, army shirt. I am awake. Our heads lie on the same pillow—my face inches from his cheek. My eyes are fixed upon his face, gazing in wonder, memorizing him.

As I look at the old black and white photograph of him and me, I see an image of a handsome young man, age thirty-five, and his infant daughter. We lie side by side on a soft, chenille bedspread. He is asleep, turned on his left side facing me. His arms are folded across his chest, slightly creasing the front of his starched, khaki, army shirt. I am awake. Our heads lie on the same pillow—my face inches from his cheek. My eyes are fixed upon his face, gazing in wonder, memorizing him.

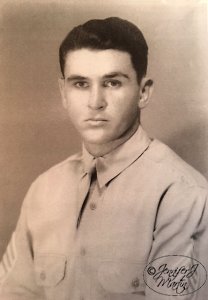

Maybe that was the day I fell in love with him? Perhaps it was when he first held me in his arms and whispered my name—the day I was born. Somewhere in the days between birth and my fourth birthday, I became his sweetheart and he became my hero. Idols and super heroes shine best during their prime. So it was with my father. His life included two important roles that he was destined to fulfill—as soldier and champion boxer. He was magnificent at both.

In 1929, at fifteen, he left his widowed mother and their rural home in Macon, Georgia to pursue his dreams. Through determination and one white lie about his age, he was accepted into the U.S. Army at McPherson, Georgia, beginning a thirty-year education in learning perfection, discipline and duty. Nineteen days short of his twenty-third birthday, he became a First Sergeant—the youngest to be appointed to that rank since World War I. He was later promoted to Master Sergeant.

As a boxer, he fought in three classes for the U.S. Army team: welterweight, middleweight and light heavyweight. They called him Jo Jo, but he had such a beautiful body they nicknamed him, “The Adonis.” His chest, biceps and forearms still bear the nine tattoos he purchased for a dollar each in Panama in 1929. I recall how the blue ink images once glistened in the summer sun against his cocoa-buttered, tan skin. The images of a sailor girl, a good-luck horseshoe and a seahorse were three dimensional as they stretched over his pectoral muscles, bulging biceps and forearms.

As a boxer, he fought in three classes for the U.S. Army team: welterweight, middleweight and light heavyweight. They called him Jo Jo, but he had such a beautiful body they nicknamed him, “The Adonis.” His chest, biceps and forearms still bear the nine tattoos he purchased for a dollar each in Panama in 1929. I recall how the blue ink images once glistened in the summer sun against his cocoa-buttered, tan skin. The images of a sailor girl, a good-luck horseshoe and a seahorse were three dimensional as they stretched over his pectoral muscles, bulging biceps and forearms.

Next to being a soldier and a boxer, my father’s other passion in life was fishing. On Sunday afternoons we could be found sitting in Old Man Foster’s boat, drifting around Lake McQueeney. I wasn’t good at fishing, so my father spent most of the day either freeing my hook from underwater grasses or yanking it loose from low-hanging cypress trees. He baited my hook repeatedly while cussing and grumbling under his breath.

“You’re more trouble than you’re worth. Next time, I’m leavin’ you at home,” he would say.

But somehow when it was time to go fishing again, he had forgotten his threat and how much money he had spent on worms. We tried hunting together once, but I spent most of the day crying over a dead rabbit.

Through the years, my father gave me a lot of advice, none of it bad. He was the only enlisted man in our family, but army life and its regulations had a way of spilling over into my world. He occasionally held inspection on my room. If I passed, I was rewarded with a quarter. He taught me to always do my best and to do things right the first time. In my teens his advice was always the same, “Keep your nose clean.” Translated from army talk, that meant, “Behave yourself and stay out of trouble.” My dad read the obituaries daily, calling them “The Casualty List.” He would say, “It’ll usually be a good day if you don’t find your name on it.”

I recall only one exception he made to good advice he once gave me. It was a bad day for me. For some adolescent reason that I cannot now recall, I was crying. My father told me to stop. “Crying is a sign of weakness,” he said. That was one of his lines to which he only gave lip service; and it was one I never bought.

Over the years, we cried together many times. It usually had to do with the tender love we shared for one another. His eyes glistened with tears whenever I told him, “I love you Daddy.” We were famous for crying every time we watched the movie On Golden Pond together. My mother jokingly referred to us as “a couple of sissies.”

The Loss of my Child

But years later when I broke the news that my only child had died, my father didn’t cry. My son, Kelly, had died at twenty-three of a heart attack. My father watched me struggle with my pain during the first two years following my son’s death. I knew it was equally hard for him and my mother, as they had helped raise him. My dad had been the only father figure my son had known; it had to feel like losing a child of his own.

I know he must have cried about it, but he never did so in my presence. Perhaps he felt he had to be strong for me and my mother. One afternoon I had taken flowers to my son’s grave. On my way home, I stopped at my parents’ house. I spoke briefly with my mother in the kitchen, trying desperately to hide my pain. The grief I was feeling broke free, and I collapsed into a dining room chair. Tears, hot and full, streamed down my face.

My father was sitting in his chair at the head of the table and told me in a firm, yet gentle tone to stop crying.

“Baby, I can’t fix this. We’ve got to accept it.” His words angered me. I wanted comfort, not a lecture. I wanted to be a little girl again, have him hold me on his lap, kiss away my tears and tell me that everything was going to be okay. At the time, his words seemed harsh.

But in the years since my son’s death, I have been able to find the wisdom in his words. Sometimes father’s can’t fix everything that is broken. Twice following my son’s death, the immensity of my grief was so overwhelming that I considered taking my own life, but my father’s words and his deep love for me were a lifeline for me to hold onto as I worked through the pain and loss.

A Secondary Grief

A time of preparatory grief approached now with the aging of my father. Over the period of many years, he had suffered four heart attacks, had bypass surgery and a partial hip replacement, and now walked with a cane. His proud, snapping gait had faded into a slow, paced shuffle. His sparkling, sometimes rascally, hazel-green eyes had lost their glint. Cataract surgery closed his right eye in a permanent “Popeye” wink. He would say of his fixed wink, “The docs botched the job.” My father had the tired look of a man betrayed by time and a body that was giving out. When my mother referred to him, she would say, “Poor thing .”

A time of preparatory grief approached now with the aging of my father. Over the period of many years, he had suffered four heart attacks, had bypass surgery and a partial hip replacement, and now walked with a cane. His proud, snapping gait had faded into a slow, paced shuffle. His sparkling, sometimes rascally, hazel-green eyes had lost their glint. Cataract surgery closed his right eye in a permanent “Popeye” wink. He would say of his fixed wink, “The docs botched the job.” My father had the tired look of a man betrayed by time and a body that was giving out. When my mother referred to him, she would say, “Poor thing .”

There is a deep sadness attached to the physical changes I saw happening to my father, like watching a great mountain slowly return to the earth, eroded to dust by time and wind. Time and events changed my father. The soft summer days of him thumping out the best, sweet, ripe watermelon were gone. The shrill sounds of katydids still lingered in the warm, summer night air, but now the scents of my father’s warm cocoa-buttered skin and freshly-mowed grass only mingled together in my childhood memories. His days of stepping into Old Man Foster’s boat and re-balancing his body had floated away. Jo-Jo wouldn’t box a couple of quick rounds again, or even one slow one.

My father died on January 22, 1998 at the age of eight-four. The tattooed images of roses, reptiles and the beautiful woman standing atop a butterfly were flat on crepe-paper thin skin where his muscles had withered. Most of the tattooed letters were illegible by then, having formed into dark, blurred pools.

Though my father’s vitality and part of his memory had faded, he held the details of his army career and championship boxing days in a crystal-clear space. For that, I was grateful. He and I traveled back often to those glory days. He took us both there instantly, recalling each and every detail. Sometimes, I read his old commendation letters to him, and he relived the moment in slow motion, savoring it. Looking at me with teary eyes, he would say, “Bet you didn’t know that about your old dad, did you?”

Though my father’s vitality and part of his memory had faded, he held the details of his army career and championship boxing days in a crystal-clear space. For that, I was grateful. He and I traveled back often to those glory days. He took us both there instantly, recalling each and every detail. Sometimes, I read his old commendation letters to him, and he relived the moment in slow motion, savoring it. Looking at me with teary eyes, he would say, “Bet you didn’t know that about your old dad, did you?”

Then there were the days when I would ask him how he was doing. He would reply, “I’m just waiting for Him to call me.”

“You know, Daddy,” I responded, “I think that when we get to Heaven, two things happen. We won’t be sick or old anymore, and God will use our greatest gifts to help Him run the place in an orderly fashion.”

My dad smiled as I told him that perhaps God would put him in charge of newly recruited angels—those who are in need of a little spit and polish. Perhaps their wings are not yet straight or their halos are askew. I described to him the formation of a band of young souls, and even gave him a cadence he could use in their training:

We are angels, we’ve been told,

Walkin’ down these streets of gold.

Got our halos cleaned up right;

They’re so bright; they shine at night.

Sergeant Joe is pretty tough;

He makes sure we strut our stuff.

See that patch there on his wing?

He’s in charge of everything.

I assured my dad that God would probably give him a few days furlough before re-assigning him. I continued telling the story, saying that I was sure that god had noticed the superior job he did of transforming hundreds of young recruits into fine soldiers during his army career. I told him it was even quite possible that he would receive a commendation.

My dad’s voice broke a little and he said he’d tell God, “Thank you, Sir.”

My father smiled. He seemed pleased with the idea of this kind of heaven—a place where he could return to his days of legend and fullness. He said, “That would be nice, Baby.”

Saying Goodbye

My father’s funeral services were held at Fort Sam Houston Post chapel. There, I stood at the side of his casket and gazed down at my father’s face for the last time. I traced my fingertips over the faceted, ruby-colored stone set in his U.S. Army ring, then laid my head on his chest and cried softly. I didn’t need to memorize anything about him anymore. It’s not required when you know things by heart.

My father’s body was transported to Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery. I stood in the Texas sun as seven young soldiers formed a row, and fired off three volleys from their rifles, equaling a twenty-one-gun salute. With a look skyward, I raised my hand in salute to the memory of a great soldier, a championship boxer and my father.

I know my father entered the gates of paradise, welcomed by old army buddies and family. He had a lot of catching up to do with everyone as he waited for his new orders. Once again, he took his new post and proudly carried out his duties. On his days off, it’s likely that he and his grandson will go fishing. That would be nice.